My experience porting the game Number Nibbler from LÖVE to Godot

Recently, I’ve been learning about the game engine Godot. As someone who loves C#, prefers free and open source software, and would like to publish to as many platforms as possible, Godot seemed promising, since it checks all of those boxes.

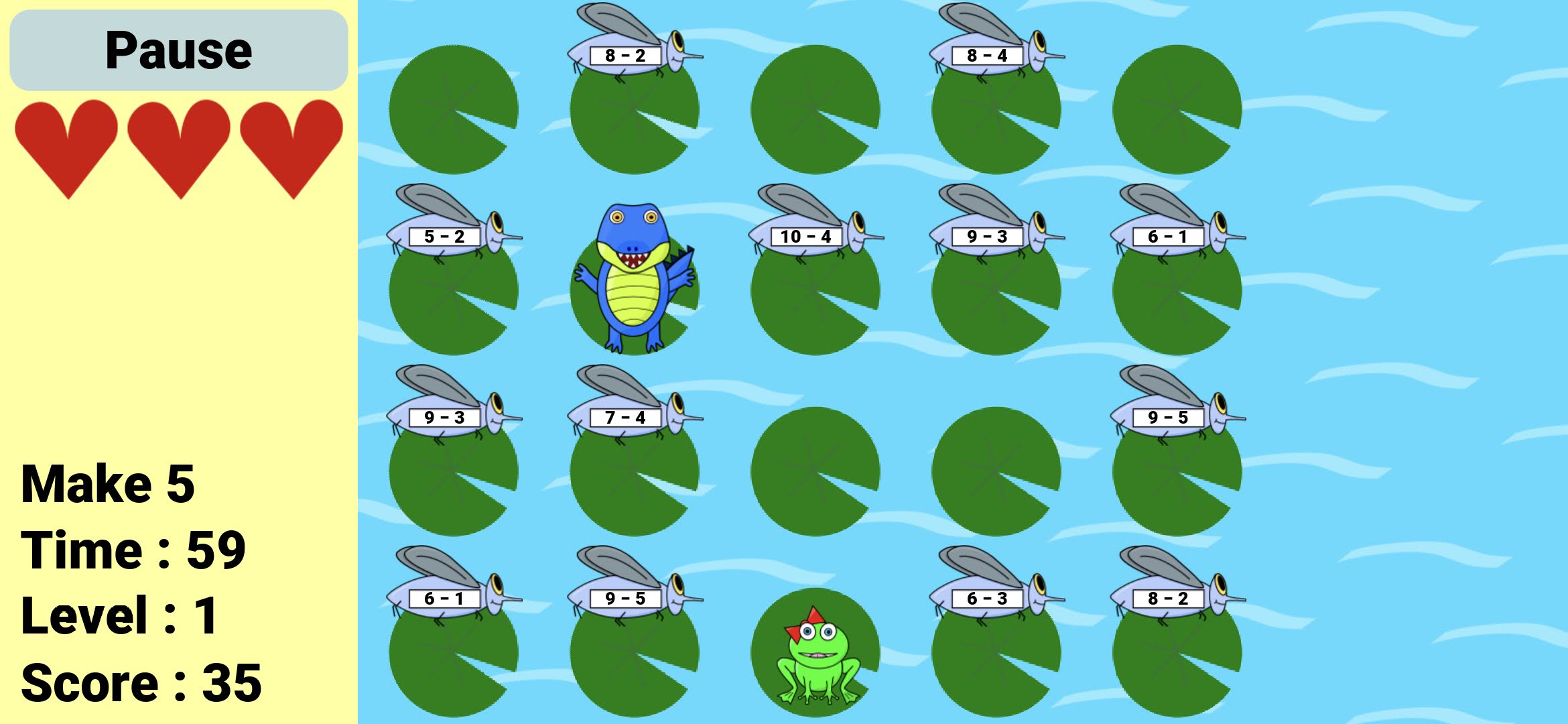

To evaluate Godot, I decided to convert a game I created a few years ago in LÖVE2D. The game I converted is Number Nibbler, an educational math game inspired by the old DOS game Number Munchers.

In Number Nibbler, players control a frog, and must jump between lily pads selecting flies that correspond to the correct answers to a listed math question.

Working with LÖVE, this game originally took me a few months to create. My prediction was that a rewrite in Godot would take much less time, for a few reasons:

- The image and sound assets had already been created, and could be reused. As a programmer, creating art is not my strength, so skipping this work would definitely be a time-save

- The basic concepts and logic of the game have already been established. Lua and C# are different languages, so translating between them would take some effort, but not as much as starting from scratch

Still, I wanted to make sure I was properly learning Godot, and using features like Nodes, CollisionObjects, Timers, Signals, and GUI Control objects. In comparison, LÖVE is a really lightweight framework, essentially an update loop with convenience methods for input, sound and drawing. That’s not a negative - the simplicity of LÖVE is what drew me to using it in the first place - but it does mean that converting from LÖVE to Godot required studying up on a lot of Godot’s features.

What were the big differences between LÖVE and Godot?

Game/Scene Editor

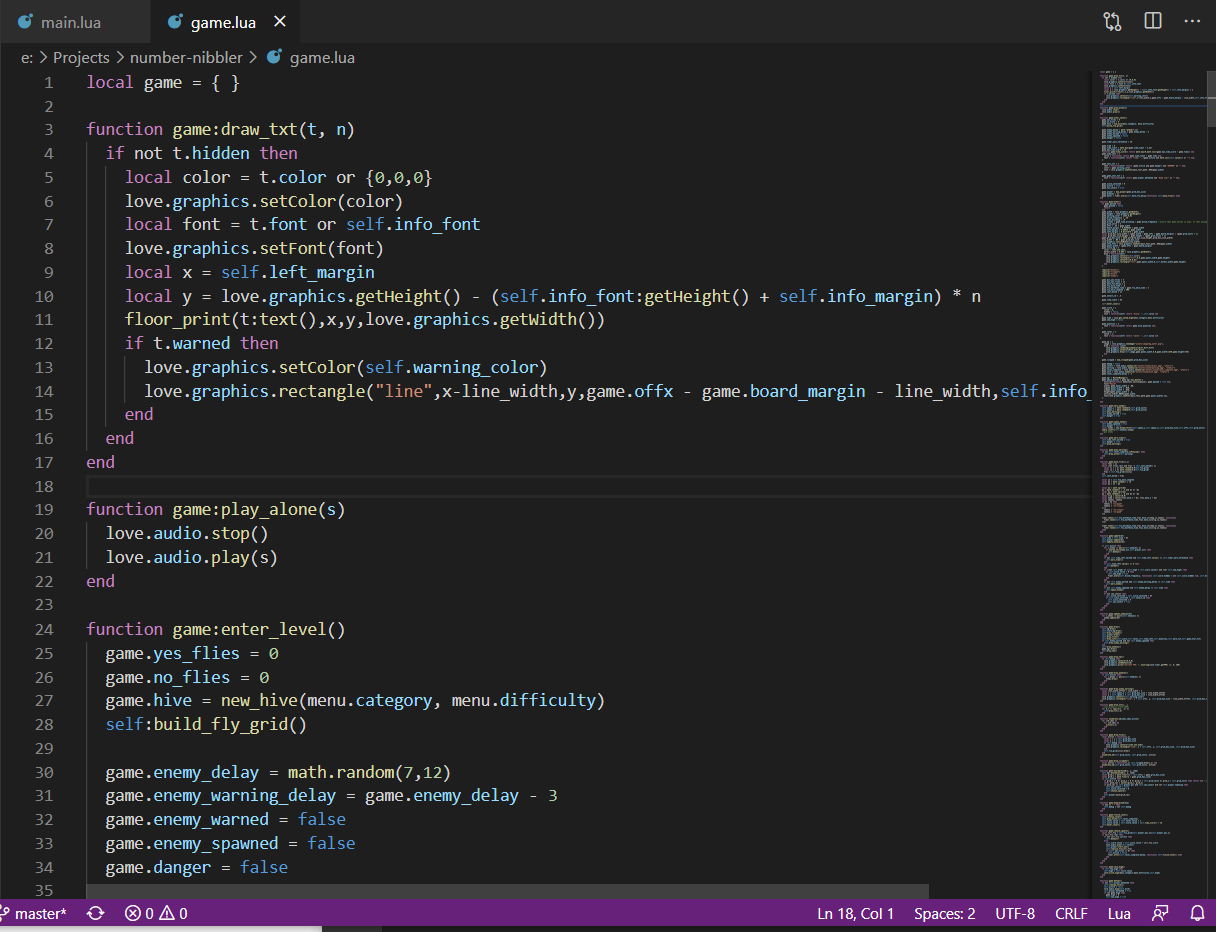

This was the most readily apparent difference between LÖVE and Godot. With LÖVE, I was almost always looking at raw code:

The core game script in Number Nibbler (LÖVE version)

LÖVE was less intimidating to get started with. I only had a few lines of code to worry about, and they were closely under my control. But that same simplicity became a hindrance as my project got bigger. Placing one sprite through code was convenient. Placing a dozen sprites in that manner started to feel haphazard and unmaintainable.

In Godot, I was able to view, edit, and organize my levels, characters, and GUI in the editor. I was impressed with how smooth it was to jump back and forth between code and the Godot editors. Godot’s editors let me explicitly define a meaningful game hierarchy, which helped me keep track of everything in my game. Just being able to see the impact of changes without launching a new game instance and reaching the relevant state was a major boon. Having worked with the Godot editor, I feel it would now be hard to go back to a code-only framework.

The Godot editor, featuring a Number Nibbler “Level” scene

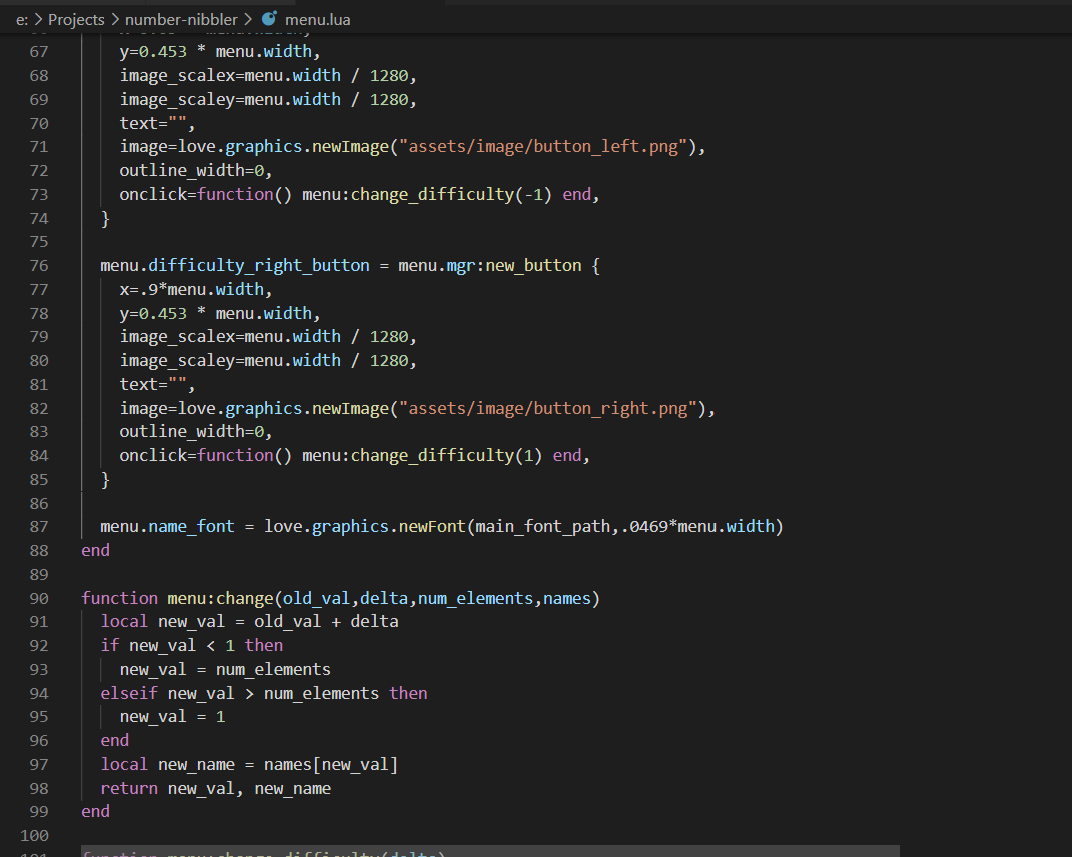

User Interface (Godot’s Control nodes)

To borrow some programming terminology, creating an interface in LÖVE required Imperative programming, while working in Godot felt like Declarative programming, or perhaps not programming at all - I simply created the GUI elements I wanted and let them fire signals off to my actual classes with game-relevant logic. As I added elements to the screen in Godot, I could let them rely on their parent container to reposition siblings appropriately. This was much easier than manually adjusting a bunch of x/y offsets for the entire UI whenever something had to be repositioned.

A portion of my main menu script defined in LÖVE. This file was 134 lines long, and relied on a 205 line custom button implementation.

In Godot, the corresponding controls were instead defined with the scene editor.

It would be unfair to judge LÖVE for lacking a robust GUI library, since LÖVE is meant to be a lightweight framework that’s easy to get started with. But even for my limited needs (a game state display, a few small menu screens), Godot was definitely superior.

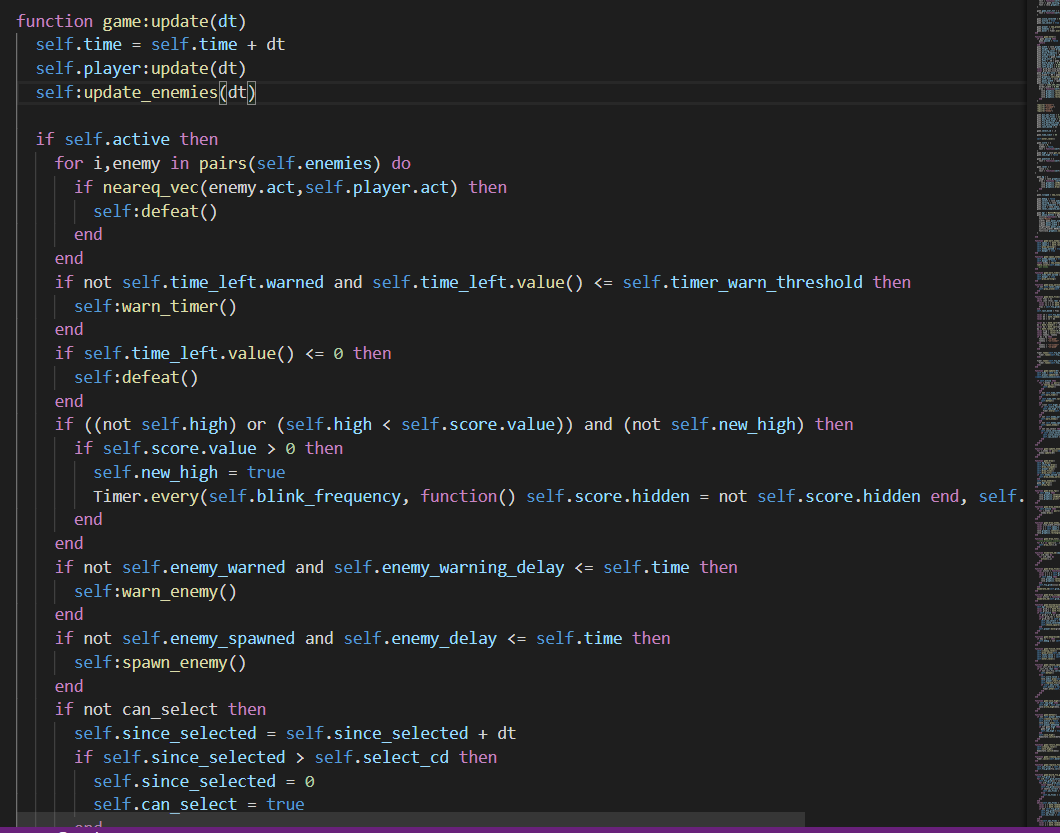

Cross-entity interactions

Core game loop in LÖVE. Each additional game entity, timer, or UI concept requires a new branch or function call

In LÖVE, development begins by creating a file called main.lua . This becomes the entry point to the game loop, and any game dependencies must be explicitly configured and called from this file (or from another file referenced within main.lua). This high degree of coupling makes it trivial to coordinate different game objects, because they directly create and have references to each other. However, this can quickly turn into a double-edged sword as game scope inevitably expands. Because each object is directly connected to other objects, changing the interface of one object can break any of the other objects which are closely connected to it.

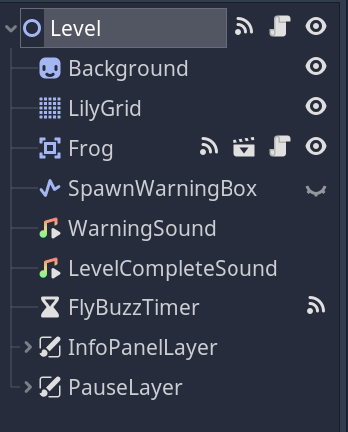

The scene tree of a level in Godot. There is a hierarchy of game elements organized here, but they’re not directly dependent on each other to function.

Inter-object communication in Godot can be handled via Signals, essentially a Publish-subscribe model where the publisher doesn’t know what (if any) classes are subscribed to it, and the subscriber doesn’t need to know which classes publish topics to it. This degree of separation ensures that behavior can safely be swapped in and out of classes with minimal side-effects. For example, when the player character is hit by an enemy, it fires a FrogHealthChanged signal that causes the Health UI to lose a heart, and the Level class to check whether the player has lost all health and a Game Over state should be triggered. These connections are loosely coupled but easily understood, the gold standard in software development.

How well does Godot live up to expectations?

C# support - mostly first class

I’m incredibly glad Godot supports C#, since it’s the language I’m most familiar with and use at work. However, there were a few snags I ran into during development:

- To get Visual Studio working with Godot, I first had to download a vsix extension (not a big deal). This extension also didn’t work, until I searched around and found this GitHub Gist with a helpful workaround.

- I wanted to have HTML5 as a target platform, and I was pleased to see that HTML5 export is supported with C#. After testing my project in HTML, I noticed some strange stuttering/artifacts when playing back sound. Online searching suggests that this can be resolved by using [Threads Export type], but this export mode is not supported for C#.

- Some Godot features, like Tweens and Signals, require typing in GDScript snake-style text literals corresponding to Godot properties. This required a fair amount of digging and trial-and-error attempts to get these methods working.

Ultimately, none of these issues were dealbreakers (and Godot does show a warning dialog for C# projects indicating that C# support is considered alpha stage). When I was learning about Godot I saw very mixed feedback on whether or not C# in Godot was a viable option. In my opinion, C# with Godot is viable, but not quite as seamless as using GDScript. As a fan of C#, I’m happy to work around the occasional quirk to use my preferred language with Godot.

Game Engines exist for a reason

Obvious, right? At some level, it’s a no-brainer that engines exist to simplify common scenarios that arise in game development. I think I had previously accepted this premise, but worried that using an engine like Godot would constrain how I had to implement my game. This never happened, and instead I was able to write the game in a fraction of the original LÖVE version by being able to take advantage of Godot’s built-in libraries and features. Animation, interface creation, etc. were a breeze, and were made even easier to use by the thorough documentation available on Godot Docs and elsewhere on the web thanks to the robust Godot community.

LÖVE is still great

While I anticipate switching to Godot for future projects, I want to affirm that LÖVE is still a really cool framework. Its ease of use helped me to get started with game creation, and I really value the knowledge I gained digging building up a game from a lower level of abstraction. I don’t think I’ll go back to LÖVE, but I do think that using it helped me to better understand certain details of game engines that previously felt black box to me. LÖVE is incredibly valuable as a tool for quick prototyping and iteration.

Summary

I’m definitely happy I decided to do a “trial run” of Godot by recreating a game I had already made. In the future, I will certainly do the same if I pick up another new tech stack. Based on my experiences, learning new game frameworks and engines is similar to adopting new programming languages. It can be helpful to learn a variety of design patterns and programming paradigms. But eventually, it’s best to settle on a technology and create something valuable. For me, Godot will be the game-dev technology of choice going forward.